Resist Loss Model for the EUV Stochastic Defectivity Cliffs

The EUV hydrogen plasma solves the mystery.

The occurrences of notorious stochastic defects in EUV lithography have resulted in CD or corresponding dose windows with the lower and higher bounds being characterized as “cliffs” [1-3], since the defect density increases exponentially when approaching these bounds. The defects at lower doses have been attributed to the shot noise from absorbed photon density being too low, while the defects at higher doses can be attributed to non-EUV exposures of the resist, such as electrons, ions, and radiation from the EUV-induced plasma, or secondary electrons from the substrate [4]. In particular, the exposure to the hydrogen is known to result in etching of the resist [5,6].

Recent data [7] have shown that an increased EUV dose led to a reduction in resist thickness (after development). The hydrogen-induced etching of the resist is a low-hanging fruit for causing this effect. A higher EUV exposure dose requires slowing the wafer stage scan speed (thus also reducing wafer throughput), resulting in a longer exposure to the EUV-induced hydrogen plasma. This leads to extra etching of the resist, leading to added resist loss. The reduction in the remaining resist thickness (after develop) can be linearly fitted to the dose [8]. Consequently, the absorbed dose in this remaining thickness can be calculated as a function of the incident dose, as well as the initial thickness.

Absorbed dose

= (Incident dose)(Transmission)(Absorption)

where Transmission = exp(-absorption coeff. x [resist thickness lost])

and Absorption = (1-exp(-absorption coeff. x [remaining thickness]).

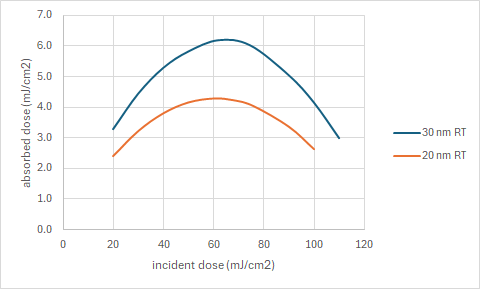

The physical understanding is clear: increased resist loss reduces the dose that is transmitted to the remaining thickness of the resist layer, and at the same time reduces the amount of resist absorption in this remaining layer. This calculation is applied to the data from [7], with initial thicknesses of 20 nm and 30 nm (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Absorbed EUV dose in remaining resist thickness as a function of incident dose, for a state-of-the-art EUV resist at 16 nm half-pitch [7]. 20 nm and 30 nm initial thicknesses are shown. The absorption coefficient is taken to be 5/um.

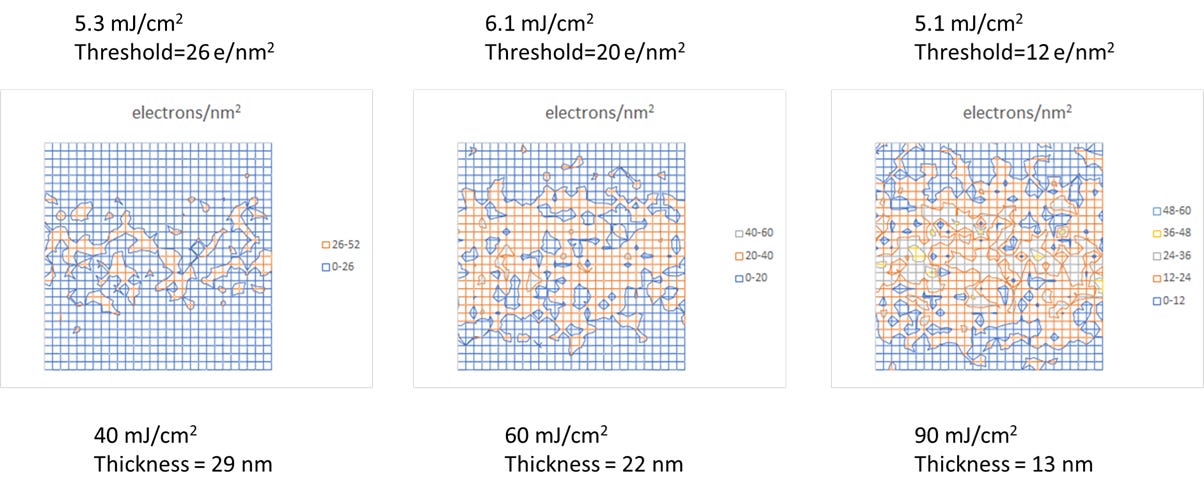

The key result is that there exists an incident dose (in the 60-70 mJ/cm2 range shown in Figure 1) for which the absorbed dose in the remaining resist reaches a maximum value. This should mark the minimum risk for stochastic defects, the valley between the defect cliffs. There is consistency with past simulations [9] (Figure 2), if we recognize that thinner resists would have lower thresholds, due to less volume to react after absorption.

Figure 2. Stochastic defectivity trend is qualitatively shown for three different doses for the 30 nm initial thickness case of Figure 1. The threshold was taken as proportional to the thickness after exposure/develop. The dose too low leads to mostly unexposed in the middle of the feature, while dose too high leads to unwanted exposure beyond the nominal feature edge.

For the 30 nm initial thickness case in Figure 1, this leads to a maximum value of the averaged absorbed photon density of ~4 per square nanometer. With a standard deviation of 2 absorbed photons (~50%) per square nanometer, the stochastic behavior is obviously expected for this 32 nm pitch case. For the 20 nm initial thickness, the absorbed photon density is even lower, ~3 per square nanometer, which aggravates the stochasticity. The resist loss is also increased as pitch decreases, and can be considered negligible for pitches as large as 250 nm [10]. This is also consistent with stochastic defects being a greater concern for smaller pitches.

Metal oxide resists have been considered a hopeful candidate as a next-generation EUV resist, due to the larger absorption coefficient (20/um vs. 5/um) [11]. However, their starting thickness is ~20 nm [12], and it is generally thinned down further [2, 13, 14]. Thus, the benefit of a higher absorption density is somewhat reduced and the stochasticity can still be quite significant. For example, 16 photons absorbed per square nanometer still has a significant standard deviation of 25%. There is also an added complication from the tin residue remaining in the areas that are supposed to be unexposed [2,8].

The EUV-induced plasma solves the mystery of the origin of the valley between the stochastic defect cliffs. Finding an appropriate resist requires not only sufficient absorption but also sufficient resist remaining after exposure to the EUV hydrogen plasma.

References

[1] P. De Bisschop and E. Hendrickx, "Stochastic printing failures in EUV lithography," Proc. SPIE 10957, 109570E (2019).

[2] N. Miyahara et al., “Fundamentals of EUV stack for improving patterning performance,” Proc. SPIE 12498, 124981E (2023).

[3] H. S. Suh et al., “Dry resist patterning readiness towards high-NA EUV lithography,” Proc. SPIE 12498, 1249803 (2023).

[4] F. Chen, Non-EUV Exposures in EUV Lithography Systems Provide the Floor for Stochastic Defects in EUV Lithography

[5] P. De Schepper et al., “H2 plasma and neutral beam treatment of EUV photoresist,” Proc. SPIE 9428, 94280C (2015).

[8] F. Chen, Resist Loss Prohibits Elevated EUV Doses

[9] F. Chen, Predicting Stochastic Defectivity from Intel's EUV Resist Electron Scattering Model

[10] D. Schmidt et al., “Line top loss and line top roughness characterizations of EUV resists,” Proc. SPIE 11325, 113250T (2020).